Across India, ancient stones tell stories of power, faith, and cultural exchange.

In the forests of Chhattisgarh, a 6th-10th century CE stone inscription and relief from the Bhima Kichak temple in Malhar stands as a silent witness to the Somavamshi era, depicting legends of Shiva and epic narratives.

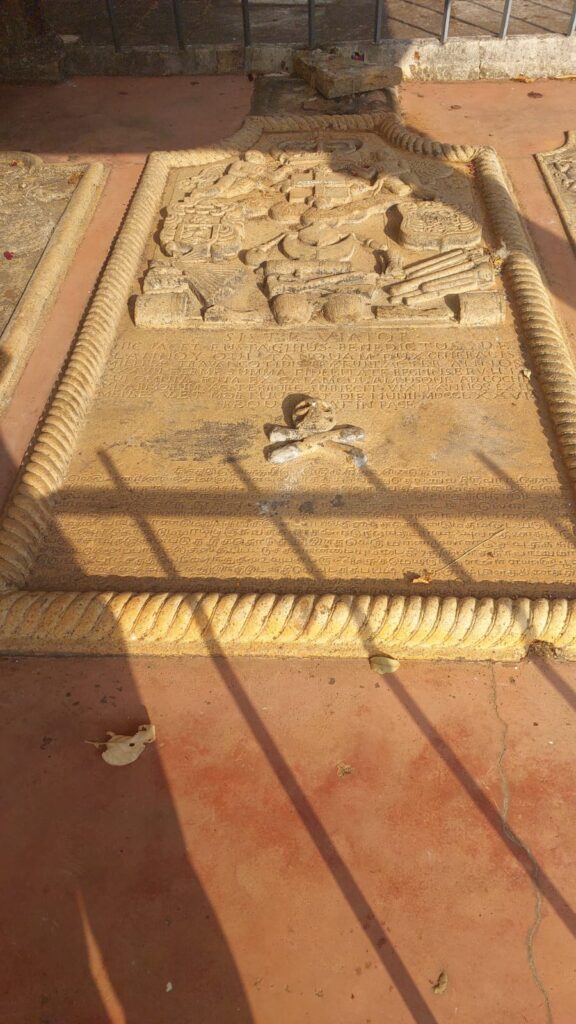

Over a thousand kilometers south and nearly a millennium later, another set of stones in Kerala’s Udayagiri Fort tells a vastly different, but equally compelling, tale from the 18th century.

Here, the multilingual tombs of De Lannoy and Fullé Kurichiy (1777 AD) reveal a complex colonial world. De Lannoy, a captured Dutch commander, became the architect of the Travancore army under King Marthanda Varma.

His companion, possibly an indigenous Kurichya warrior leader, shares the same honored memorial. Their inscriptions in Tamil and Latin bridge two worlds, much as the sculpted gods in Malhar connected the divine and the earthly.

The drama of the era is captured in the cryptic note on “Proteste Monnet,” an army demonstration demanding the release of General Peter Flory, who was abducted in 1777. This act of defiance highlights the tensions within a hybrid military force.

Together, these sites—one a fragment of early Hindu temple art, the other a colonial-era epitaph—show how stone endures as the permanent archive of history, recording everything from ancient epics to the loyalties, conflicts, and protests of a rapidly changing world.

By James Kisoo