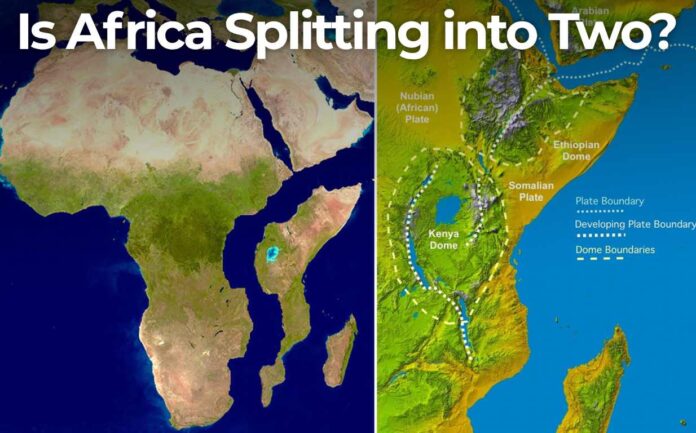

A recent study indicates that Africa is gradually splitting in two, a process that began millions of years ago. Scientists from Keele University analyzed magnetic data to uncover signs of geological separation between Africa and Arabia.

Once seamlessly connected, the two land masses are slowly drifting apart. The process, spreading from northeast to south across the continent, is accompanied by volcanic and seismic activity.

“When this split is complete — perhaps in 5 to 10 million years — Africa will consist of two distinct land masses,” said Professor Peter Styles, a geologist at Keele University.

The larger western mass would encompass countries such as Egypt, Algeria, Nigeria, Ghana, and Namibia, while the smaller eastern mass would include Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, and much of Ethiopia.

The Role of Plate Tectonics

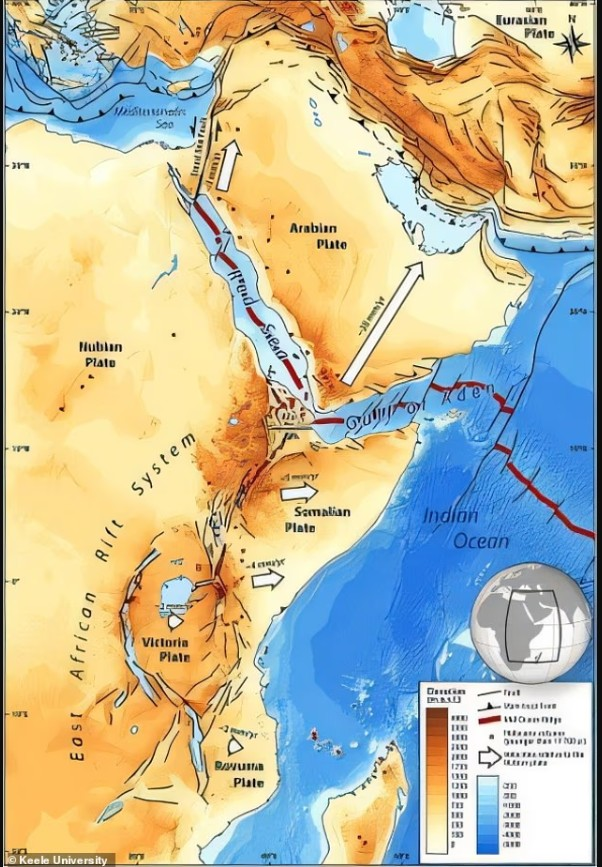

The theory of plate tectonics explains that the current configuration of the continents has dramatically shifted over geological history. Large tectonic plates have broken apart and drifted over millions or billions of years, forming new oceanic crust in a process called seafloor spreading.

Researchers point to the East African Rift, one of Africa’s largest tectonic features, as driving the slow continental rifting.

Stretching approximately 6,400 km from Jordan to Mozambique, with an average width of 50–65 km, the rift will eventually separate large lakes in East Africa, including Lake Malawi and Lake Turkana.

Afar: A Geological Hotspot

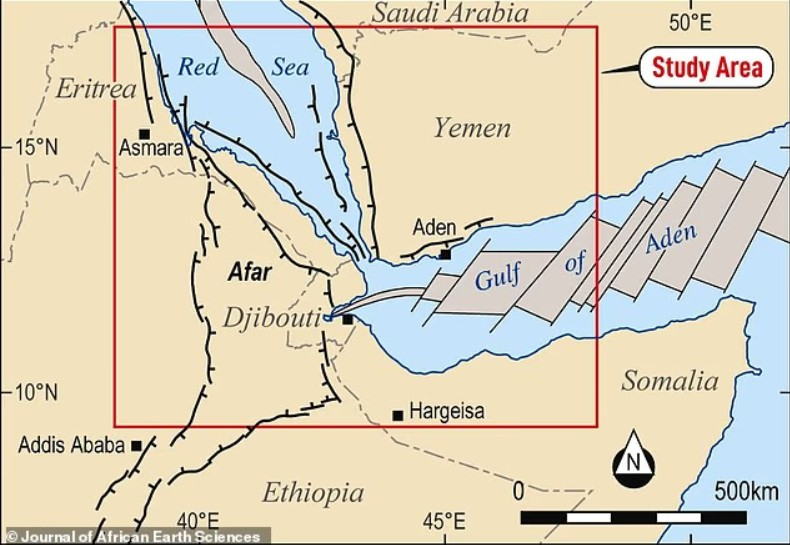

The study focused on the Afar region, where the Red Sea converges with the Gulf of Aden. This area is unique in hosting a triple junction, where the Ethiopian Main Rift, Red Sea Rift, and Gulf of Aden Rift meet.

“Here, we are witnessing the early stages of continental drift, a process that has been unfolding for millions of years,” said Dr. Emma Watts, a geochemist at Swansea University.

Magnetic data collected in 1968–1969 using airborne instruments revealed signs of finite ocean expansion between Africa and Arabia.

These signals suggest that the continent is stretching and thinning slowly, and may eventually split, marking the formation of a new ocean. Dr. Watts notes that the process is ongoing, with movement occurring at a rate of approximately 5–16 mm per year in the northern part of the belt.

Tectonic plates, which include the Earth’s crust and upper mantle, move atop the asthenosphere — a warm, viscous layer of rock. Earthquakes primarily occur at plate boundaries where one plate slides beneath or past another, though old geological faults within plates can also reactivate.

According to the study’s authors, the Afar region offers a rare natural laboratory to study continental separation and the early stages of ocean formation, providing valuable insight into the dynamic processes shaping the Earth.