In a discovery that challenges long-held theories of planetary formation, astronomers have detected a Saturn-sized planet orbiting an unusually small star, prompting scientists to rethink how such massive planets can form around low-mass stars.

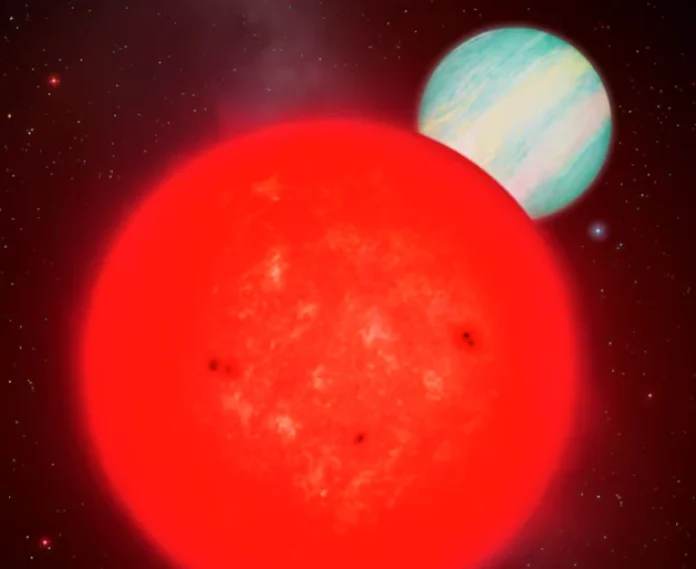

The star, named TOI-6894, lies approximately 240 light-years away in the constellation Leo and is just 21% the mass of our sun. Despite its diminutive size, TOI-6894 hosts a gas giant roughly the same diameter as Saturn, the second-largest planet in our solar system, making it the smallest-known star to harbor such a large companion.

“This is a surprising find,” said Edward Bryant, lead author of the study published Wednesday in Nature Astronomy and an astronomer at the University of Warwick. “The question of how such a small star can host such a large planet is one that this discovery raises, and we are yet to answer.”

The planet, which completes an orbit in just three Earth days, is located about 40 times closer to its star than Earth is to the sun. Its mass is about 56% that of Saturn and only 17% that of Jupiter, making it less dense but still substantial.

Planets typically form from a protoplanetary disk of gas and dust left over after a star’s birth. But smaller stars form from smaller clouds, theoretically leaving less material to build giant planets. “In small clouds of dust and gas, it’s hard to build a giant planet,” explained Vincent Van Eylen, a study co-author and exoplanet scientist at University College London. “There’s only so much time before the star ignites and the disk dissipates.”

TOI-6894 is a red dwarf, the smallest and most common type of star in the Milky Way and is about 250 times dimmer than our sun. Its planet, however, is unusually close in size: while our sun’s diameter is ten times greater than Jupiter’s, TOI-6894 is just 2.5 times wider than its planet.

“This discovery forces us to rethink some of our planet formation models,” Van Eylen said. “It suggests that even the smallest stars in the universe can, under the right conditions, form very large planets.”

The team used data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile to detect and study the planet. Future observations with the James Webb Space Telescope aim to uncover more about the planet’s composition, which scientists expect includes a large rocky core and a thick atmosphere of hydrogen and helium.

“Given how common red dwarfs are in our galaxy,” Bryant noted, “this could mean that giant planets may be more widespread than previously thought.”

Written By Rodney Mbua