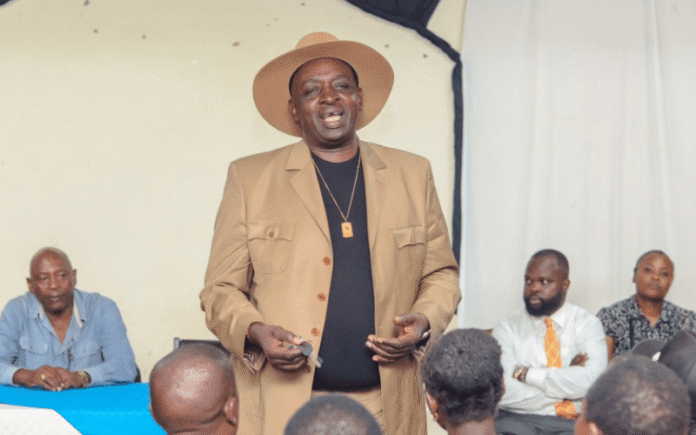

Embakasi North MP James Gakuya’s assertion that “President Ruto needs ODM more than anything else” has stirred debate, but beneath the provocation lies a reading of Kenya’s political terrain that many analysts quietly agree with. As the country inches toward the 2027 General Election amid economic pressure, political fatigue, and shifting alliances, ODM’s relevance to President William Ruto’s survival strategy has arguably never been higher.

President Ruto governs in an environment far more complex than the one that delivered him victory in 2022. His Kenya Kwanza coalition secured power with a narrow margin, leaving his administration perpetually vulnerable to parliamentary rebellion, street pressure, and regional political fragmentation. ODM, as the country’s most organized opposition party with a national footprint, controls not only numbers in Parliament but also legitimacy among key voter blocs, particularly in urban centres, Coast, Western, and parts of Nyanza.

From a parliamentary standpoint, ODM’s cooperation has already proven crucial. The passage of contentious legislation, including finance bills and economic reforms demanded by international lenders, has required cross-party backing. Without ODM votes, the government risks legislative paralysis or embarrassing defeats that could weaken executive authority. In this sense, ODM has shifted from being merely an opposition force to a political stabiliser—one that the Ruto administration increasingly depends on to function.

Beyond Parliament, ODM’s importance lies in its ability to calm or ignite the streets. Kenya’s history shows that sustained opposition mobilisation can grind governance to a halt. ODM, under Raila Odinga’s long-standing influence, has unmatched capacity to mobilise mass action or, just as critically, to restrain it. For an administration grappling with high cost of living, youth unrest, and public sector discontent, ODM’s restraint has effectively acted as a buffer against nationwide instability.

Gakuya’s remarks also speak to electoral mathematics. Ruto’s Mt Kenya base, once solid, has shown signs of fatigue and fragmentation. At the same time, ODM’s traditional strongholds remain numerically decisive. Any credible path to a comfortable 2027 re-election requires either neutralising ODM or incorporating it. A cooperative ODM reduces the risk of a united opposition front and allows Ruto to project an image of national unity rather than regional dominance.

However, this dependence cuts both ways. ODM’s engagement with the government carries political costs for the party itself, including internal dissent and accusations of betrayal from its base. This imbalance fuels Gakuya’s argument: that ODM is propping up the government more than the government is empowering ODM. The perception that Ruto gains stability, votes, and breathing room while ODM absorbs internal backlash strengthens the claim that the ruling side needs the opposition more than it admits.

There is also a governance angle. International partners and investors tend to favour political inclusivity and predictability. ODM’s presence—formal or informal—in the governance conversation reassures external actors wary of political shocks. For Ruto, this translates into economic credibility at a time when Kenya is navigating debt restructuring, IMF conditions, and fragile public confidence.

Yet reliance comes with risk. Should ODM withdraw cooperation or fracture internally in a way that reactivates confrontational politics, the government would face a legitimacy and stability crisis.