By John Mutiso

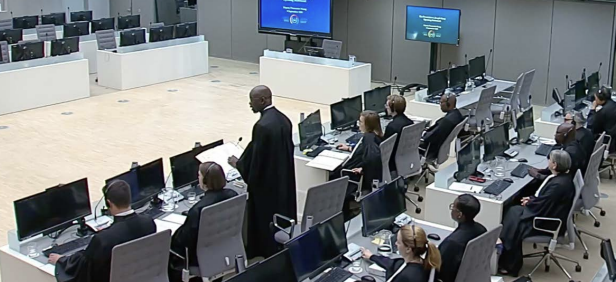

The International Criminal Court (ICC) has formally closed its investigation into the 2007–2008 post-election violence in Kenya but is still pursuing two Kenyans accused of interfering with witnesses.

According to the latest report to the Assembly of States Parties, the Office of the Prosecutor announced on 27 November 2023 that it had concluded all investigations related to the Kenya situation, effectively ending a 13-year pursuit of accountability for the violence that left more than 1,000 people dead and displaced hundreds of thousands.

At the height of the ICC process, six prominent Kenyans faced charges of crimes against humanity: former President Uhuru Kenyatta, President William Ruto, former Cabinet minister Henry Kosgey, former Head of Public Service Francis Muthaura, former Police Commissioner Mohammed Hussein Ali and journalist Joshua arap Sang. They all denied the allegations.

Between 2013 and 2016, the cases collapsed due to insufficient evidence, withdrawn testimony, and what the Court described as widespread witness interference and political meddling. Deputy Prosecutor Nazhat Shameem Khan said the failures reflected a systematic breakdown of evidence, attributed largely to intimidation and manipulation of witnesses.

While the main investigative phase has ended, the ICC says it is not completely disengaging from the Kenya situation. Its focus now shifts to preserving the integrity of the Court’s judicial processes.

Two active arrest warrants remain for Kenyan fugitives Walter Barasa and Philip Kipkoech Bett, both wanted for alleged offences against the administration of justice under Article 70 of the Rome Statute. They are accused of corruptly influencing or attempting to influence ICC witnesses—actions that prosecutors believe played a critical role in undermining the core cases.

“They are the subject of warrants of arrest for alleged offences against the administration of justice pursuant to Article 70 of the Rome Statute, consisting of corrupting or attempting to corruptly influence ICC witnesses,” the report states.

Witness tampering had long been cited as a major obstacle to the Kenya cases. In 2014, charges against Kenyatta were withdrawn after prosecutors said witnesses had been intimidated or interfered with. The case against Sang was dismissed shortly after.

In 2016, the ICC terminated the case against President Ruto. Although the judges found insufficient evidence to proceed, one judge declared a mistrial, citing an “intolerable” level of political interference and a “troubling incidence” of witness tampering. Ruto had denied charges of murder, deportation, and persecution during the violence, in which about 1,200 people were killed.

The ICC’s decision effectively closes the chapter on international legal proceedings stemming from the 2007–2008 violence. For many victims and families, the collapse of the cases and the absence of convictions represent a painful reminder of unresolved injustices.

More than 500,000 people were forced to flee their homes during the violence, marked by targeted attacks and deep ethnic and political divisions. Despite numerous inquiries and reconciliation efforts, no senior figure has been held accountable for orchestrating or enabling the conflicts.

The ethnic tensions and trauma from that period remain deeply felt today, with critics saying the collapse of the ICC cases leaves key questions unanswered about responsibility, truth, and compensation for victims.