In the annals of African leadership, few figures loom as large as Jomo Kenyatta, the founding father of Kenya.

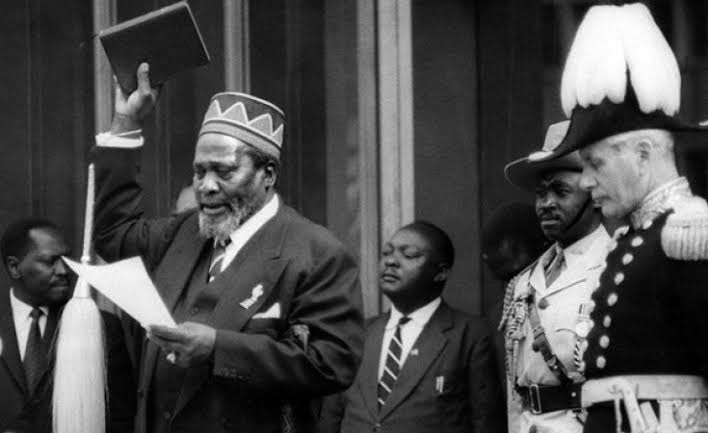

As the nation’s first president, Kenyatta was not only central to the country’s struggle for independence but also a nuanced player in the broader narrative of Pan-Africanism.

Unlike revolutionary leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah, Kenyatta’s approach was characterized by a distinct pragmatism—one that deftly balanced Pan-African ideals with Kenya’s pressing national interests.

Kenyatta’s foreign policy, a cornerstone of his presidency, was defined by the principles of gradualism and diplomacy.

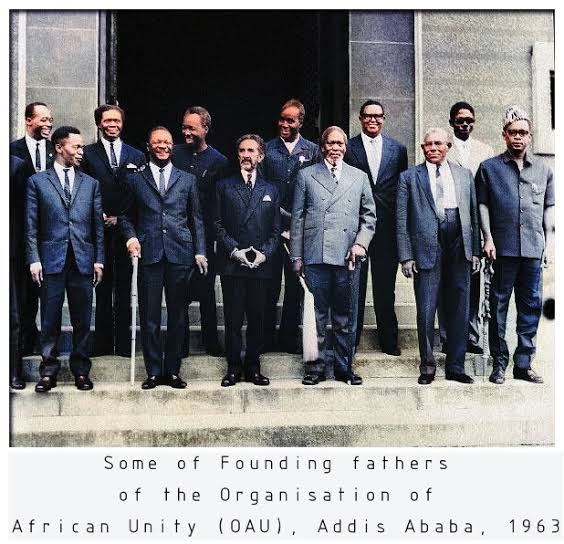

His role in the establishment of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963 underscored his commitment to fostering African solidarity while resisting the pervasive forces of neocolonialism.

This initiative was emblematic of Kenyatta’s vision: he sought unity among African states, but did so through pragmatic means that, to some, may have appeared less idealistic than those adopted by his contemporaries.

Despite his exposure to Marxist-Leninist ideas during his early years—from friendships with activists like George Padmore to his time spent in the Soviet Union—Kenyatta ultimately distanced himself from these ideologies.

Instead, he embraced a more centrist perspective, integrating concepts gleaned from his years in Britain and his interactions with Western liberal democratic models.

By the time he assumed leadership, Kenyatta dismissed Marxism as a useful lens through which to analyze Kenya’s socio-economic challenges.

He was adamant that aligning with Western interests was not an act of dependency but rather a strategy for national development.

The Cold War backdrop positioned Kenyatta as a stabilizing figure amid regional tumult. His administration astutely navigated the intricate geopolitical landscape of the era, leaning towards the West while maintaining a stance of non-alignment.

This duality allowed Kenya to leverage substantial foreign direct investment, particularly in agriculture and infrastructure, propelling the nation’s economic growth during his tenure.

The West, viewing Kenyatta as a moderate, responded favorably, resulting in an inflow of capital that would benefit many Kenyans.

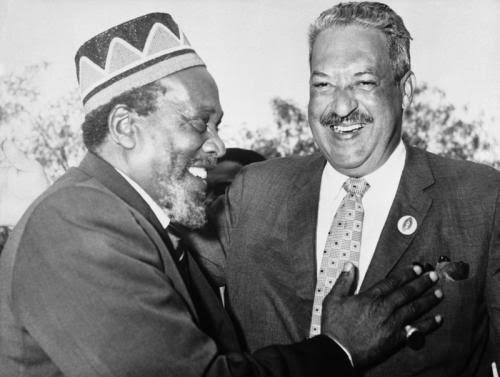

Kenyatta’s legacy is intertwined with his vision for a reconciliatory Kenya—a nation that embraced its diverse ethnicities while forging ahead with a unified purpose.

Known affectionately as Mzee, or “respected elder,” he was heralded as the Father of the Nation. His policies initially garnered support from both the black majority and the white minority, a delicate balance in a post-colonial context still fraught with ethnic tensions.

However, Kenyatta’s presidency was not devoid of criticism. His rule faced allegations of authoritarianism, nepotism favoring his Kikuyu ethnicity, and the corrosive effects of systemic corruption.

Detractors argue that while Kenyatta preached tolerance and peace, the realities of governance reflected an increasingly dictatorial approach.

Yet, even amid such challenges, Kenyatta’s aspirations remained clear: “I have stood always for the purposes of human dignity in freedom, and for the values of tolerance and peace.”

His vision for a self-determined Kenya, where every citizen could develop according to their own wishes, encapsulates the complexity of his leadership.