Kenya has become the first country to secure a direct government-to-government health financing agreement with the United States, in what officials on both sides are calling a historic shift in development cooperation.

Under the new Health Cooperation Framework, Washington will inject $1.6 billion (KSh 208 billion) into Kenya’s health sector over five years. Crucially, the money will go straight into state institutions rather than non-governmental organisations, marking a departure from decades of donor practice.

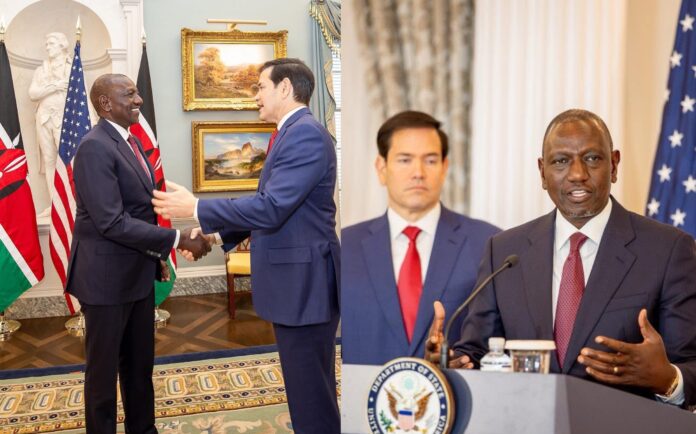

President William Ruto, who witnessed the signing in Washington alongside Prime Cabinet Secretary Musalia Mudavadi and US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, described the deal as validation of his administration’s universal health coverage agenda. He said the investment would modernise hospital equipment, strengthen supply chains, reinforce disease surveillance, and expand access to the Social Health Authority’s services.

Ruto cast the agreement as recognition of Kenya’s capacity to manage its own healthcare funding. He promised accountability, insisting that “every shilling and dollar” would be used efficiently. The president framed the partnership as an evolution of a long-standing relationship under which the US has poured more than $7 billion into Kenya over the past 25 years.

Washington offered its own rationale for the shift. Rubio said Kenya was chosen because of its strong institutions, arguing that traditional donor models diverted money into NGO overheads rather than national systems. The new arrangement, he said, is about backing partners directly rather than outsourcing development to third parties.

Rubio also praised Kenya’s leadership in the Haiti security mission, insisting the country “cannot do it alone” and urging more states to contribute money and personnel. Ruto said Kenya would maintain its role in Haiti with continued international backing.

The weakening of USAID funding hits at the soft underbelly of the country’s public health machinery. HIV programmes that relied heavily on American support are reporting stock gaps, reduced community outreach, and shrinking access to prevention drugs.

Clinics that once depended on donor-backed supply chains now face delays, and the national system is forced to stretch thin budgets to patch holes it was never prepared to fill.

Health workers speak of a familiar story: increased patient loads, reduced services, and anxiety over how long stopgap measures can hold.

Progress Kenya made over the past two decades in keeping HIV infections down and strengthening disease response risks being rolled back.

The shock landed just as Nairobi is selling its universal health coverage reforms and promising stronger health institutions, making the cuts a politically inconvenient reality.