Kenya’s efforts to stabilise its mounting public debt are being undermined by weak institutional oversight and political inertia, according to the latest Africa Economic Brief by the African Development Bank (AfDB).

Despite having one of the most elaborate legal frameworks for fiscal governance in Africa, the report finds that Kenya’s Parliament and Debt Management Office (DMO) lack the technical depth and coordination needed to manage borrowing effectively.

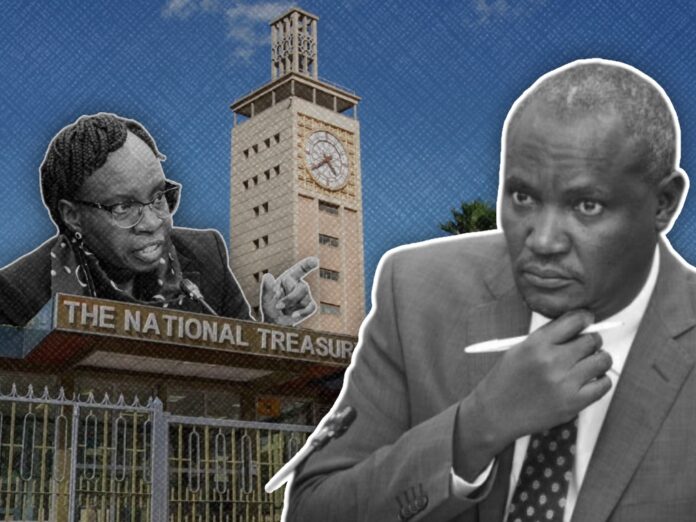

The AfDB says that Parliament, though constitutionally empowered to set borrowing limits and oversee debt policy under Article 211 of the Constitution and Section 32 of the Public Finance Management Act, often fails to exercise this authority fully. Analysts at the Institute of Economic Affairs describe the legislature as largely “rubber-stamping” executive borrowing decisions, raising concerns about the independence of fiscal oversight.

The DMO, housed within the National Treasury, also struggles with limited capacity to assess loan risks, forecast repayment stress and monitor contingent liabilities. This has led to heavy reliance on short-term, high-interest instruments such as Treasury bills, which drive up domestic debt servicing costs. The Office of the Auditor-General, mandated under Article 229 of the Constitution to audit public debt annually, faces similar resource and data challenges.

To address these weaknesses, the National Treasury has initiated several reforms, including integrating the Public Debt Management System with the Integrated Financial Management Information System (IFMIS) for more accurate and timely reporting. It is also implementing a Treasury Single Account for all government entities to reduce unnecessary domestic borrowing. Parliament has approved a 2025 debt strategy that proposes a new working committee to track the use of borrowed funds.

Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi has acknowledged Kenya’s rising debt, which hit KSh 12 trillion by September 2025—about 68 percent of GDP. He insists the debt remains sustainable but admits that the risk of distress is high. Mbadi’s plan focuses on lengthening repayment periods, increasing concessional borrowing from multilateral lenders and tilting the debt mix toward domestic financing to reduce currency exposure.

The AfDB has urged Kenya to form an independent fiscal council to provide non-partisan oversight and improve transparency. Without stronger accountability and professional capacity in debt management, economists warn, Kenya’s borrowing strategy may continue to rely on patchwork fixes rather than long-term fiscal discipline.

![[Full List] – Safaricom, Absa and Britam Named Among Top Employers for 2026](https://uzalendonews.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Screenshot-2026-01-15-190157-218x150.png)