For decades, unemployment has remained the most persistent challenge in Kenya and across much of the developing world. The policy prescriptions have been familiar with governments being tasked to build industries, expand markets and ease the cost of doing business all whilst employers are placed under immense pressure to absorb young people into productive opportunities. These strategies have resulted in progress, but the structural crisis of unemployment has not been resolved.

The reason is clear. Traditional models of work, designed for an industrial age, can no longer absorb the millions of young people entering the labour force each year. Factories, offices and public service jobs cannot keep pace with population growth and technological change. As the global economy evolves, labour markets are being transformed by digital platforms, artificial intelligence and new service delivery models.

These emerging sectors offer opportunity, but only if we develop the right skills and reimagine how labour relations are governed. More importantly, the need for a new social contract that recognises the limits of the old system and builds pathways into the digital economy, is now more critical than ever.

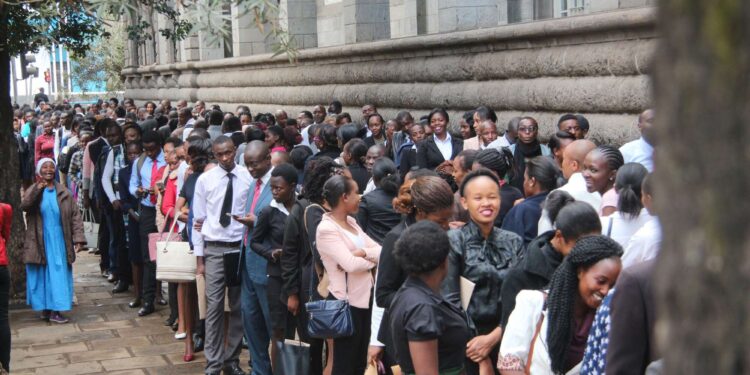

Africa stands at a decisive demographic moment. With an average age of 19, Sub-Saharan Africa is the youngest region in the world. By 2050, its population will have doubled. For Kenya, this surge of human capital represents both an extraordinary opportunity and a looming threat.

If young people are equipped for productive work, the continent can unleash a demographic dividend that powers decades of growth. If they remain unemployed or underemployed, the dividend will become a burden that erodes stability and deepens inequality.

The scale of the challenge is already stark. In Kenya, 70 per cent of the workforce requires reskilling to meet the demands of modern industry. Across the region, employers face shortages in critical skills even as millions of educated young people remain idle. This paradox of abundant but underutilised talent reflects not just an employment challenge but a crisis of alignment between education, work and economic transformation.

At the heart of this misalignment is the breakdown of social dialogue. For decades, structured consultation between government, employers and workers was the foundation of labour relations. Over time, this culture has weakened and the terrain is characterized by legal tussles, siloed policy development and adversarial tactics where cooperation is needed.

Social dialogue is critical as it will allow stakeholders to co-create solutions that match skills to industry demand, adapt regulation to new forms of work and anticipate the disruptions of technology before they harden into crises. Without it, we risk addressing unemployment through fragmented and ineffective measures that do not touch the core of the problem.

Furthermore, traditional work models cannot conclusively address the unemployment issue and neither will they deliver inclusive growth. Manufacturing jobs and public service roles cannot absorb the numbers of young people graduating each year.

New models are emerging that demand specialised but accessible skills. Unlike professions of the past that required years of training, many digital-age roles from data services to artificial intelligence support can be mastered through focused, short-term programmes.

This shift opens space for innovation in labour relations. Instead of debating how to preserve outdated structures, the country should embrace dialogue that supports workers to transition into these new sectors, while also ensuring that protections, benefits and fair conditions are not lost in the process.

Germany, if we are to draw lessons, has built one of the most resilient labour markets in the world through a strong system of vocational training rooted in social dialogue. The German Dual Training System combines classroom education with on-the-job training in partnership with employers. Workers, government and industry bodies collaborate closely to ensure that skills are continuously aligned with market needs. This system has allowed Germany to maintain low youth unemployment rates even during times of global economic turbulence.

A similar model, championed by the Federation of Kenya Employers is already in place. The Dual Technical and Vocational Education and Training Programme links training directly to industry demand. By 2024, the programme had placed 338 trainees into real industry roles, with a target of 6,000 placements across the country. While still modest in scale, it demonstrates that structured collaboration between employers, government, and training institutions can deliver real results.

Employers are also showing how the new economy can be harnessed. Sama, for example, has partnered with the University of Nairobi to build a talent pool for artificial intelligence. This initiative positions Kenya not only as a consumer of global technologies but also as a producer of the human capital that powers them.

At the Africa Employers Summit, concerns were raised that artificial intelligence could displace up to half of existing roles. Sama’s approach demonstrates the alternative: with the right skills pipeline, disruption can be converted into opportunity.

The platform economy offers another frontier. In Kenya, it already generates an estimated 64.5 billion shillings annually, or about 500 million dollars. With the right dialogue and policy frameworks, this sector can provide thousands of flexible work opportunities. Without dialogue, however, platform workers risk exclusion from labour protections and social safety nets, undermining the sustainability of this new economy.

Consequently, to position its workforce for the digital economy, Kenya requires a new social contract that reflects the realities of the digital age. This contract must rest on three pillars. The first is trust, rebuilt through structured dialogue among government, employers, and workers. The second is shared responsibility, recognising that sustainable employment cannot be delivered by one actor alone. The third is innovation in labour relations, ensuring that emerging forms of work, whether platform based, technology driven, or digitally mediated, are supported by policies that both protect workers and encourage sectoral growth.

The skills demanded by the digital economy are within reach. With targeted, practical training, young people can quickly acquire the capabilities needed to thrive in new industries. The real challenge lies in creating institutions and pathways that connect them to opportunity.

Kenya is well placed to lead this transformation. Its entrepreneurs, universities, and employers are already building foundations for a dynamic digital economy. What remains is the political impetus to make dialogue the default mode of labour relations. Traditional work models cannot deliver inclusive growth in the twenty-first century. A new social contract, adapted to the digital age, can.

Dr.Gilda Odera is the National President at Federation of Kenya Employers (FKE)

Annepeace Alwala is the Vice President, Global Service Delivery at Samasource Kenya