Professor Arthur Obel has rested. He is gone. By a distance, he was the most intelligent man I have ever met. That claim makes people bristle. But no one needs to it is only my opinion.

Those who object usually do so because they overrate their own cleverness. If I know you and you object, take comfort: I still think Obel was smarter than you. I don’t say this to offend. I say it because it is true.

He died on the 27th of September. When I first met him, I disliked him instantly. He was jocular, with a face bunched up in angles, defying beauty and leaning dangerously toward ugliness.

His teeth jutted out, though not nearly as far as his prodigious abdomen. He had come as a visiting professor of pharmacology. His text was our required reading. His biography, which I read after meeting him, was so dazzling it felt fictional ,page after page of heavyweight credentials in a field already stacked with them by the kilo.

“Young man,” he said by way of greeting at my viva voce, “I noticed you did not fully explain the mechanism of action of acetylcholine blockers in your exam paper.”

That was his hello. And here was the terrifying part: under his arm he had every script from our entire class, all fifty of them. He had read them all, marked them all, and memorized every wrong answer. When my turn came, he casually opened with a smile and began reciting my errors word for word, like a stand-up comic roasting his audience.

“Tell me again, slowly, how atropine works. And this time, don’t murder the poor receptors.”

I tried. He laughed. I sweated. He quoted me back to myself, line for line. And then, for good measure, he threw in the mistakes of three of my classmates and demanded I correct them on the spot. It remains the single greatest display of mental power I have ever witnessed. I walked out dazed, staggering, and secretly convinced I had met a mind from another planet.

He visited twice more, and I warmed to him. The arrogance was Kilimanjaro, but the brilliance was undeniable. A PhD in medicine from the University of London. A member of the Royal Society of Physicians. A masters on top of that. Obel was the kind of man who made degrees look like bus tickets, always another one in his pocket.

And he was rich. In this field of academic Medicine, genius usually pairs with poverty, men who can recite entire books in their sleep but cannot pay rent. Not Obel. He was irascible, hot-tempered, supremely self-centred, but he had the mind (and the appetite) to convert thought into shillings.

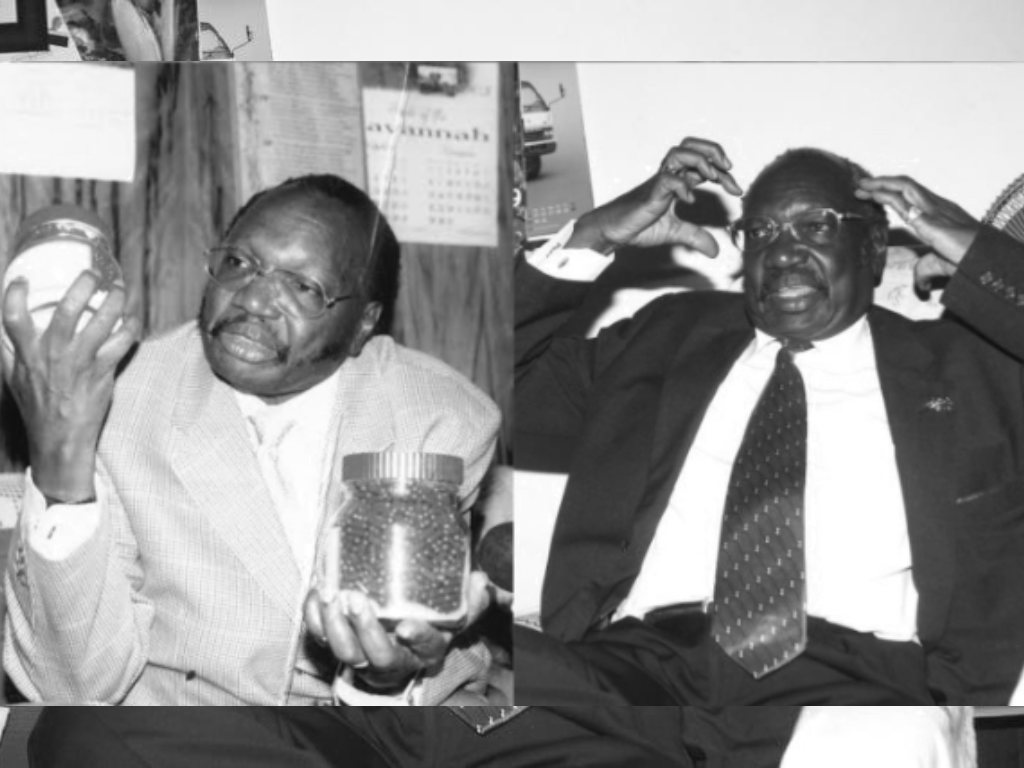

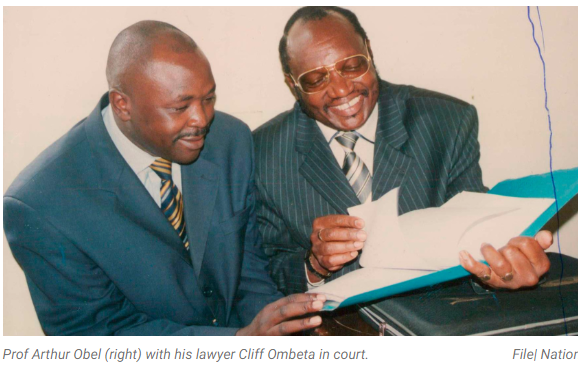

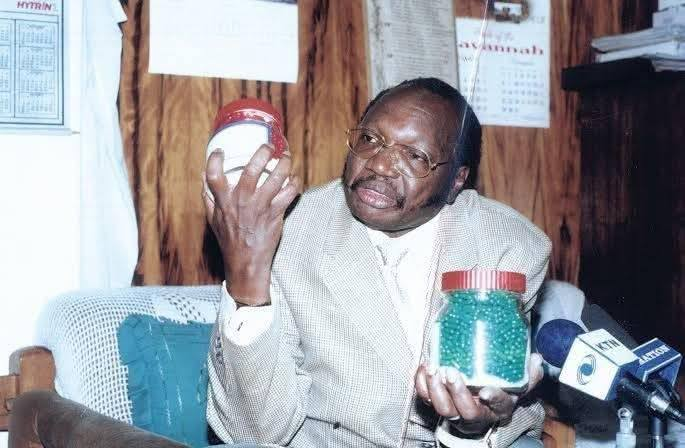

He also had the madness. Like many geniuses, his brilliance came laced with delusion. He invented an “HIV cure” called Pearl Omega, sold it for thousands, and conned desperate patients. He carried two pistols and occasionally unholstered them during ward rounds while berating medical students.

And then there was the matatu incident. One evening, after a quarrel with a driver, Obel pulled out his gun and shot him. He was arrested, charged, paraded through court. And yet this is the awkward truth, many of us cheered. If you’ve ever been nearly killed by a matatu, if you’ve ever been insulted by a tout while handing over your last twenty shillings, you know that tiny, guilty flicker of recognition.

Obel acted out the fantasy Nairobians joke about in traffic jams but never dare confess aloud. He crossed the line. We winced. And we clapped.

Picture it: a ward full of trembling students, Obel waving a gun with one hand, a stethoscope with the other.

“You call that a differential diagnosis? I think you should think of an easier career…maybe journalism”

Yet you couldn’t look away. He drove expensive cars, never combed his hair, and always managed to leave a trail of chaos and awe behind him.

I am certain, even now, he is at the gates of heaven arguing with St. Peter.

“Pearl Omega worked! You just didn’t understand the protocol.”

“Professor,” St. Peter sighs, “this is the line for repentance, not peer review.”

SOURCE : UoN Alumni